Navigating the History and Rise of Private Credit: A New Frontier in Lending

Exploring the Surge in Private Credit Markets and Its Implications for Modern Finance

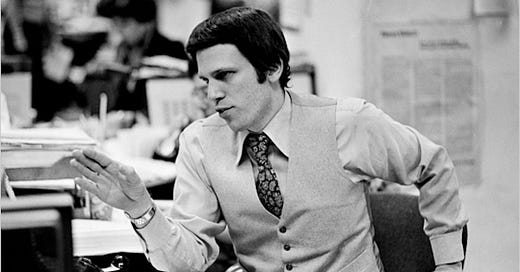

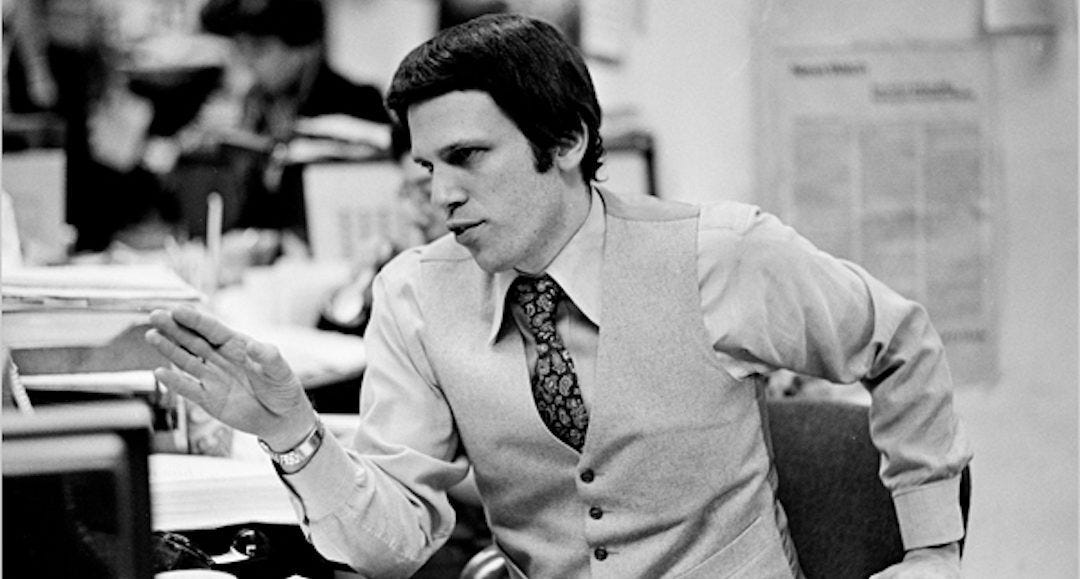

“Financing is an art form. One of the challenges is how to correctly finance a company. In certain periods of time, more covenants need to be put into deals. You have to be sure the company has the right covenant -- to allow it the freedom to grow, but also to insure the integrity of the credit. Sometimes a company should issue convertible bonds instead of straight bonds. Sometimes it should issue preferred stock. Each company and each financing is different, and the process can’t be imitative”

Michael Milken

Before we start

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. A considerable amount of effort has been poured into its creation, with the aim of presenting the intricacies of private credit as clearly and simply as possible. My hope is that you've gleaned as much insight from reading it as I did in the process of writing it. Your thoughts and perspectives are incredibly valuable to me, and I welcome any reflections or comments you might have. Let's keep the conversation going and continue to learn from one another

Introduction to Private Credit

Private credit is the hot thing on Wall Street right now. Not a day goes by without someone proclaiming it’s the “Golden Age” of private credit on Bloomberg. According to BlackRock, the asset class has more than tripled since 2015 to $1.6tn in global assets under management, but amidst the noise, it's essential to cut through to the core: what exactly is Private Credit, and why is it becoming so prominent?

Let's break it down. Private Credit is essentially when a non-bank institution lends money to businesses, often small to medium-sized, that aren't hitting those top-tier investment grade marks just yet. This type of credit is a breath of fresh air in a private investment portfolio because it doesn't dance to the tune of the equity market fluctuations. The bonus? It serves up a shorter J-curve, thanks to the regular payback you get from loan repayments.

But let's translate that into real-world terms:

Imagine you're at the helm of a budding tech startup. Demand for your product is skyrocketing, orders are tripling, and now there's a golden opportunity to break into a new market—let's say Brazil. These are the kind of problems you want to have! However, to meet this new demand and tap into the Brazilian market, you need significant capital. You need to beef up your engineering team by 100 and establish a new factory and team in Brazil.

You've run the numbers. The projections look sweet—the investments would pay off. Naturally, you stride into a bank with a solid plan and a business case. But banks, with their risk radar, aren't too keen on a company that's been around for less than a decade. So, there's the rub. You're stuck with a grand vision but no financing to back it.

Behind The Deal Comment: If you've been keeping up with recent articles, this narrative might seem familiar to you. It resembles the tale of Phil Knight striving to expand his company while banks refused to lend him money. If you haven't read the Nike saga, I have left a link to the first part just here

Enter the alternative options you dig up during your research: Private Equity/Growth Equity and Private Credit Funds. You weigh them up. Private Equity might mean new partners and a network of strategic alliances, but you're hesitant to sell a slice of your dream. On the other hand, Private Credit Funds are less about partnership and more about a financial transaction—they’re willing to bet on a riskier profile like yours without demanding a stake in your company.

This is where the world of Private Credit swings opens its doors to you—a comprehensive solution for companies caught in the growth spurt burn, offering a feasible path to scale without parting with equity.

Private credit investing is much like buying a bond, with the main difference being that private credit isn’t traded on the public markets and typically isn’t available to the general investing public

As investors in private credit are making loans, rather than acquiring an ownership stake, they are more likely to be repaid if the borrower faces bankruptcy. In addition, there is a chance for diversification, with the flexibility to invest in different types of loans with distinct risk/return profiles. Private loans often have floating interest rates, which can benefit investors when rates increase.

Historical Growth of the Private Credit Industry

To fully grasp the ascension of Private Credit and its importance, we must explore its genesis and the factors contributing to its current boom. Is Private Credit an indispensable cog in the financial machine, or is it a surplus driven by market exuberance? When conversations about Private Credit spill over into casual chats with your taxi driver, it prompts us to question whether the industry is overcapitalized. Let's delve into the evolution of Private Credit to discern its true significance and necessity in the financial landscape

The 5 core pillars in the history of private credit

The 5 more important components in the rise of private credit are:

A New Kind of Debt: Think of Michael Milken as a debt wizard at a firm called Drexel Burnham Lambert. He made it popular to lend money to smaller companies through something called high-yield debt. He also taught a lot of today's private credit big shots.

Rules for Banks: Over the years, especially since the 1980s, banks have had more rules to follow, making it tough for them to lend money to medium-sized companies. This opened up a spot that private credit stepped into.

The wave of American banking consolidation: Big American banks have been joining forces, which means they're now more interested in dealing with really large companies. That's left the smaller ones for private credit to help out.

Private is Popular: These days, companies prefer staying private rather than going public, and they're backed up by lots of private investment money. This means there's a big market for private credit to dive into.

The Market Swings Post-COVID: After COVID hit, there's been a surge in company buyouts, changes in interest rates, and some loans didn't go as expected. This situation has made private credit a go-to pick for funding big company purchases.

While these reasons line up over time, private credit's rise is a mix of different forces. There have been highs, lows, and lots of changes to rules, all leading to private credit and private companies getting more in sync over the past 50 years.

1. A New Kind of Debt

High-yield bonds, also known as "non-investment grade bonds," might sound fancy, but essentially they're loans that are a bit risky. Even big names like Tesla, Uber, and Hilton have these bonds. Today, they're pretty normal and can be part of a regular investment mix, but it wasn't always this way.

Back in the early '70s, these bonds were like the fallen stars of the finance world. Banks wouldn't touch them for fresh loans, and the only ones floating around were from companies whose financial rep had taken a hit after they'd borrowed the money.

During his college days in the 60s, a guy named Michael Milken spotted some research that showed that a large, diversified portfolio of low-grade bonds (aka “High Yield bonds” or non-investment grade bonds” produced better returns than a large, diversified portfolio of high-grade bonds. The low-grade portfolio incurred more defaults, but the higher yield more than compensated for the incremental losses.

After his MBA at Wharton, Milken takes this idea to Drexel Firestone in 1970 and starts working his magic with these high-yield bonds, making decent money, but he's kind of the odd one out, he was viewed as a pariah and constrained to a small capital base in an isolated corner of the firm.

Years later, Drexel merged with Burnham & Company, and the new CEO, Tubby Burnham, recognized Milken's potential. Milken received control of a $2 million portfolio and a deal for the 35% of his trading profits. In his first year, Milken's portfolio yielded a 100% return.

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure

By the early '70s, a lot of mid-sized companies needed money because the usual banks that helped them were teaming up and moving on to bigger fish. When Fred Joseph joined Drexel as co-head of corporate finance in 1974, he decided they'd specialize in helping these "medium-sized, emerging companies," which meshed well with Milken's focus.

Legend holds the term “junk bond” originated during a conversation between Meshulam Riklis of Rapid-American and Michael Milken when Milken proclaimed, “Rik, these are junk!” Riklis responded, “You are right! But they pay interest, and they sell at a discount.” To Milken’s disdain, the joke stuck.

The new wave of junk bond issuance began in earnest in early 1977 when Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb underwrote several new issues of low-grade, high-yield bonds. These issues were a stark contrast to the existing fallen angels, as they were rated sub-investment grade from the start, a move not seen since the conglomerate boom of the 1960s. By 1977, Milken had cultivated a substantial client base of junk bond advocates. Between 1974 and 1977, his clients saw significant gains from trading junk bonds from companies such as Loews, Westinghouse, and Woolworth's.

Milken's Impressive Run

For the next decade, Milken and Drexel are on fire. By '86, they're the top dogs on Wall Street, and Milken's raking in massive paychecks. He's backing big names in business, turning them into tycoons with the help of these high-yield bonds.

Milken was also a core pillar of the 1980s LBO boom. Working alongside the head of Drexel’s M&A group, Leon Black, Milken raised billions of dollars of high yield debt for takeovers of National Can, Revlon, Beatrice Companies, RJR Nabisco, and many others. According to a study from the University of Florida, high yield bond issuance was $300m in 1977. By 1986 issuance had ballooned to over $18bn and Drexel Burnham Lambert had 53% market share.

Drexel's Downfall

But by the decade's end, things get messy. Insider trading scandals hit the headlines, and even Milken isn't immune. Drexel faces huge fines and eventually goes bankrupt in 1990.

Despite the dramatic fall, Milken's influence lingers. He helped shift financial thinking—smaller companies might be riskier, but you can win big with them.

Post collapse, Drexel alumni dispersed like seeds of a dandelion into the winds of Wall Street. Nearly all major players in today’s private credit landscape track their roots directly or indirectly to Drexel Burnham Lambert. The following map almost certainly misses some relevant Drexel alumni, but in general, paints a compelling portrait of Milken’s impact. Other firms had outsized impacts as well like Banker’s Trust, E.F Hutton, Lehman Brothers, and GE Capital, but at the end of the day…

So, that's where it all starts—a risky bond that was once trash becomes treasure, setting the stage for the intricate world of private credit.

2. Rules for Banks

The 1980s was a decade that had its fair share of financial drama. On October 19th, 1987, known as "Black Monday," the stock market plunged with the Dow Jones dropping a staggering 23%. Drexel Burnham Lambert, the firm behind the junk bond market, collapsed at the decade's close, and the U.S. witnessed a vast majority of its savings and loan associations go bankrupt. Internationally, Latin America grappled with a debt crisis. All this commotion caught the attention of world governments.

Banking regulators, who had been discussing bank capital sufficiency since the 1950s, began implementing modern rules based on these risks in the 1980s. In 1983, U.S. Congress set some ground rules with the International Lending Supervision Act. Post-1988, when the Basel Capital Accord (Basel I) took effect, Congress passed two influential acts—the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (1989) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (1991)—which together sculpted the U.S. version of Basel I.

The idea was to categorize bank investments by risk levels. Depending on the risk, the assets got a weighted percentage determining the capital or equity the bank needed to back it up. Here's how it broke down:

Cash or similar: 0% (No need for extra equity.)

Short-term claims by U.S. institutions: 20%.

Home loans: 50%.

Business loans: 100%.

This new system made it particularly costly for banks to extend credit to businesses, especially for private equity deals. In simple terms, it led banks to steer clear of funding leveraged buyouts or takeovers.

As the 1980s buyout boom hit its stride, regulators narrowed in on these buyouts. In 1989, they defined what a "highly leveraged transaction" (HLT) was. Essentially, if a business deal led to huge debt spikes or doubled a company's liabilities, it fell under the HLT category.

Regulators wanted to keep tabs on HLTs because banks were deeply involved in financing takeovers, with estimations of bank involvement in U.S. LBOs at half the funding between '87 and '89. By 1989, banks' exposure to HLTs could have been a massive $170 billion, bringing about stricter oversight.

All this regulation made banks wary of lending, particularly for high-risk deals. From '89 to '94, the percentage of bank credit that went to businesses dropped, and banks started retreating from financing these risky transactions.

This retreat set the stage for the popularization of a new loan type better suited for non-banks—Term Loan B, which didn’t have to be repaid in small pieces but rather in a big chunk at the end. Banks didn’t like holding onto these due to regulatory reasons, further opening the door for other financial institutions to step in.

During Milken's time, non-bank firms had already tiptoed into the high-yield bond waters. But as banks backed away due to regulations, non-banks found their opportunity, evolving into what we now know as the private credit industry, able to serve the middle market that banks left behind.

As we turn the pages from the 80s to the dawning era of internet and telecom deregulation, investment surged, particularly in tech and telecom fields. But with newfound growth came excessive lending, leading to more layers of oversight.

Economic ebbs and flows, regulatory tugs of war, and financial creativity have all woven the fabric of modern private credit, shifting it from the sidelines to a main player in the world of corporate financing.

3. The wave of American banking consolidation

The landscape of U.S. commercial banking has drastically changed over the past four decades. From 1980's 14,434 insured commercial banks, the number plunged by over 70% to 4,136 in 2022. The trend didn't happen by chance; regulation had a significant hand in reshaping the industry.

The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 essentially opened the gates for branch banking across state lines nationwide, while the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act, empowered banks to diversify their services into other financial markets.

In a banking version of the '80s leveraged buyouts and the '90s telecom M&A extravaganza, banks have been on a merger and acquisition tear. According to the FDIC, between 1999 and 2024, we've seen a total of 8,254 "business combinations" involving various types of financial institutions.

The concentration of assets is even more striking when looking at deposits. As per S&P Global data, the top four U.S. banks—JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citibank, and Wells Fargo—together hold over 35% of all American bank deposits. When extended to the top 15, that share jumps to 56%, despite there still being more than 4,100 separate banking entities in the U.S.

Regulations like capital adequacy and risk retention limit the banks' capacity for riskier commercial lending. Consequently, the big banks have shifted focus to more lucrative large-cap loans. The time spent on a $2 billion loan is roughly the same as for a $200 million loan, but the return is significantly higher. Large corporations in need of substantial credit lines often bring in additional revenue through ancillary banking services, further incentivizing banks to prioritize bigger clients.

Now, for most banks, leveraged lending has become a question of scale: create large loan packages, distribute them among collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), maintain the minimal required balances, and profit from the associated transaction fees. This change in strategy means less personalized attention for small to mid-sized businesses and a chasm in the market that private credit is all too eager to fill.

4. Private is Popular

Banks have found themselves largely restricted from leveraging a key principle first recognized by Michael Milken in the '70s: the middle market, a crucial segment of the American economy, is ripe for financial services.

The Middle Market's Rapid Expansion The Middle Market is defined by the National Center for the Middle Market as companies earning between $10 million and $1 billion in revenue, positioned between small businesses, which often attract significant attention, and large businesses that grab headlines. JP Morgan offers a tighter definition, targeting businesses with revenues between $11 million and $500 million. Their 2023 report, "The Middle Matters," emphasizes that the middle market, consisting of 300,000 businesses and generating $13 trillion in revenue, is responsible for 30% of private sector jobs.

This market segment isn't just sizable; it's growing faster than its larger counterparts, increasing the pull for private equity and, consequently, private credit attention. Data from Pitchbook reveals a steep climb in the number of U.S. middle market companies backed by private equity, jumping from 1,700 in 2000 to almost 9,000 in 2020. With banking regulations deterring mid-market commercial lending, private credit has stepped in to fuel the growth of these substantial businesses.

A Trend Towards Keeping Companies Private The landscape of publicly traded companies in the U.S. has shifted dramatically, with a roughly 50% reduction from 8,090 in 1996 to just 4,266 in 2019, according to American University research. The lifespan of a tech company before going public has also extended, nearing three times longer today than in 1999.

McKinsey analysis shows that it's increasingly rare for smaller companies to go public, often due to the regulatory burdens post-Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) and the availability of private equity as a substitute for public equity capital. Additionally, M&A activity, closely linked with private equity, demonstrates the strength of private capital: in 2022, while public capital markets raised $1.2 trillion, private markets amassed over $4.5 trillion—almost three times as much.

Many perceive public market investors as overly focused on short-term results, pressuring companies to consistently "beat and raise." This scrutiny makes firms apprehensive about going public, considering the hefty costs and abundant private capital availability. The combination of these elements prompts many companies to extend their private status far longer than previous market norms.

5. The Market Swings Post-COVID

March 2020 saw a freeze in the global economy that led to a startling plunge of over 30% in the S&P 500 between February 14th and March 20th. However, this decline was short-lived. Propelled by the government's injection of $800 billion through non-recourse PPP loans and another $900 billion directly credited to individual accounts, the market rebounded with a vengeance. Suddenly, everyone was talking about GameStop shares peaking at $483, and Bored Ape NFTs commanding a floor price over 150 ETH. Back home, analysts scoured the internet looking for the next big leveraged buyout opportunity as they juggled between screen hunting and 'Call of Duty: Warzone' sessions.

Reflecting on this, 2021 turned out to be an exceptional year for Wall Street, with CLO sales, indicative of leveraged loan issuances, nearly tripling to a record $430 billion. The top six investment banks saw their profits soar to a whopping $170 billion, doubling their earnings.

Enter the Fed's interest rate hikes.

The Pain of "Hung Debt" Debt issuance for LBOs traditionally involves a bank offering to issue debt for an LBO upon request from a client. For example, Morgan Stanley might agree to secure $13 billion in debt to back someone like Elon Musk in an exciting takeover bid. Initially, Morgan Stanley holds the debt but plans to sell it promptly to credit market investors. When Elon Musk began amassing Twitter shares in January 2022, Morgan Stanley probably set their agreement around February when interest rates hovered at a mere 0.08%. However, in March, the Fed unrolled a series of rate hikes, resulting in an 11-quarter uptick that left buyers reluctant to purchase Twitter debt at previously agreed prices. Banks like Morgan Stanley found themselves grappling with undesirable, highly-leveraged corporate debt, stalling their underwriting activity for a heartbreaking 18 months as they unloaded these loans at substantial losses.

Twitter's troubled deal is not unique. Banks reportedly accumulated over $80 billion in "hung debt" through 2022. Despite these challenges, private credit funds have emerged victorious. Reports highlighted triumphant returns over 30% IRR for funds in deals such as Citrix's preferred equity issue, with major players like Oak Hill and KKR leading the charge. As a testament to their growing influence, private credit funds were instrumental in major financings like Oak Hill's $5.3 billion backing for Vista's Finastra.

In 2022 alone, private credit fund managers deployed over $330 billion in loans, a staggering 60% increase from the previous year. These groundbreaking deals and massive inflow in private credit funding have heralded what many dub the "Golden Age" of private credit.

What's the deal with private credit?

Let's take it back to the start, when Drexel was the king of leveraged finance and the investment grade market was a murky, uncharted territory. Michael Milken was the mastermind at his desk, dreaming up the idea of issuing new bonds for these not-so-perfect companies, a.k.a. "fallen angels."

Fast forward through financial history, and you'll see banks getting tangled in a web of regulations like the Basel Accords, Dodd-Frank Act, and those pesky HLT Guidelines. These rules made it really tough for banks to give out loans to mid-sized companies, especially for big risk, big reward private equity deals. That's when non-banks—think private credit funds—jumped in with a "we got this" attitude.

As banks got bigger and bolder, merging together and chasing after the big fish loans, they left a gap in the lending world for medium-sized businesses. That's where private equity pounced, armed with a treasure chest of funds ready to dive into that middle market.

Then, in what feels like a moment straight out of a thriller, the stimulus-injected LBO craze came to a screeching halt as the central bank flipped the script, making a U-turn on interest rates. This dramatic twist set the stage for private credit to step up their game, going after bigger and more ambitious deals.

But was this whole shift a goof-up?

Some might say that all this regulation pushed traditional banks aside, giving "shadow banks" their big break in financing the less-public side of the market. Sure, there's a bit of truth to that. But let's not call it a bad thing—sometimes, unintended turns lead to a stronger economy.

Despite regulations, private markets might have naturally gravitated this way, bolstered by a simple rule of finance: you don't want to be caught in a tight spot borrowing short-term to fund long-term loans. Private credit helps smooth out the mismatch that's tripped up even the sturdiest of financial institutions.

Banks run on customer deposits, which can magically disappear overnight, while private credit bases its bets on long-term funds from sources like university endowments and pensions. By marrying long-term, illiquid loans with stable capital, private credit not only sucks up the systemic risks but also makes the finance world a more reliable place.

Even Michael Milken, the pioneering father of high-yield debt, post-SVB collapse opines that we'll likely see a "substantial increase in private credit," backed by those who think long-term. Turns out, this whole evolution might just be a new chapter in building a more robust financial system.

As we close the chapter on this exploration into the world of private credit, I'd like to express my gratitude for your journey alongside the twists and turns of financial innovation. May the insights garnered here illuminate your understanding of the ever-evolving market dynamics. Thank you for delving into the depths with me, and I look forward to our next intellectual expedition. Until then, take care and stay curious.